History

Cinema was first introduced to Sri Lanka, then Ceylon, by European British. It was the common scenario with many South Asian and other colonized countries during that era. According to early records, the first film was screened in 1903 as a private screening to a British Governor. Later on, tent cinema screenings such as the ‘Regal Tent’ had started off from Colombo. The first three decades of the twentieth century passed with having only colonial news reels and foreign film screenings passed among the colonizers in Ceylon. The first ever effort for the local film production ‘Royal Adventure’ (1925) ended up in an unfortunate and mysterious failure, due to the loss of materials after screening in India and Singapore. Later on, W. Don Edwards’s local short film ‘Revenge’ (‘Paliganima’) was screened in 1936 as the first recorded locally produced film. Well known British documentary film, which was shot in Ceylon, about Ceylonese ordinary life, ‘Song of Ceylon’ (1934) directed by Basil Wright was a land mark, though it was not considered a local film.

The extant story of Sri Lankan fictional cinema began with B. A. W. Jayamanne’s Broken Promise (‘Kadawunu Poronduwa’) in 1947 in par with the Independence from ruling British Governance. Director Sirisena Wimalaweera also managed to compete with Jayamanne’s theatre influenced melodrama with his avid film productions and had a popular nationalistic approach to mainstream cinema of the 50s on the context of post-colonial restructuring of the state.

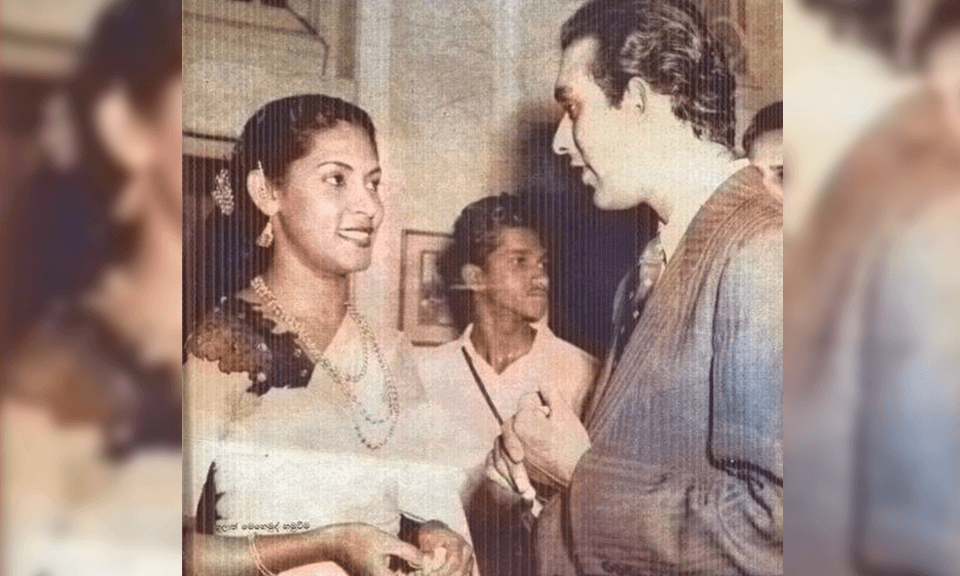

‘Line of Destiny’ (‘Rekhawa’ 1956) by Lester James Pieries, was the first revolutionary cinema production recognized by most of the critics as the real twist of Sri Lankan Cinema. It was screened and competed at the main competition of Cannes IFF in 1957 as the first Sri Lankan film ever to participate in. It received a major international recognition and a wide distribution. With Lester’s artistic and intellectual approach to art of cinema, a new generation of directors managed to break the existing classical melodrama tradition and discover a path to express their social and individual existence in a subtle cinematic language.

Soon after, the recourse, novices T.Somasekaran, Mike Wilson, Tissa Liyanasooriya and Siri Gunasinghe Sugathapala were among many experimenting with new paths in cinema. While the senior directors such as, K. A. W Perera, Robin Thampo and Shanthi Kumar continued to cater the classical Indian melodrama influenced genres simultaneously.

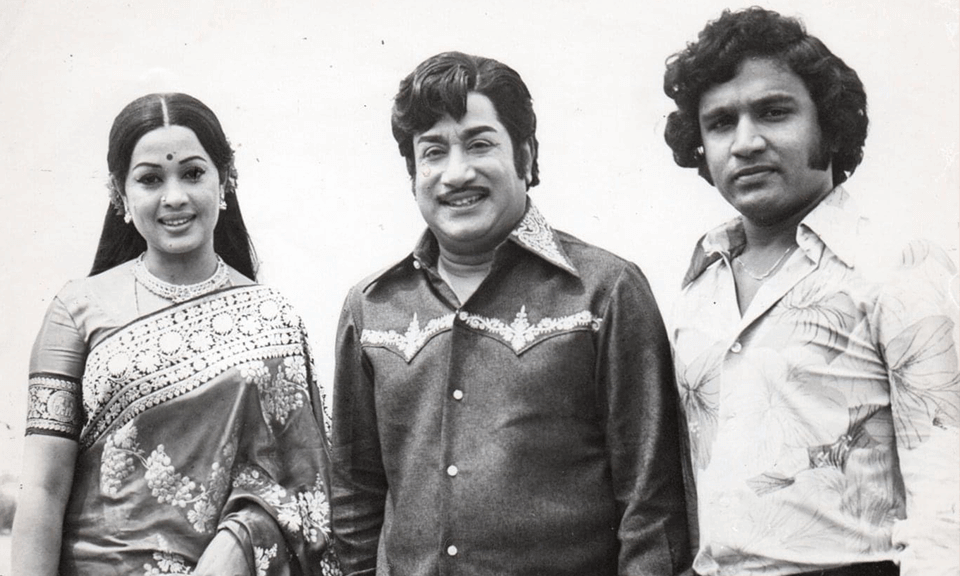

By the 60s, revolutionary mainstream fell in line with directors such as Sugathapala Senarath Yapa, Lenin Morias, M.S.Anandan, Premnath Morias, Sena Samarasinghe, Titus Thotawatte and many more. They expanded the industry to cater for a vast range of diversity beyond stereotypes. The arrival of Dharmasena Pathhiraja with his debut ‘One League of Sky’ (‘Ahas Gawwa’) in 1974 was considered a radical break of Sri Lankan political cinema and the beginning of a new left wing aesthetics. He was hailed by many radical critics and intellectuals for his bold approaches. His Tamil language film’ Ponmani’ (1978) was also a landmark among nearly 40 Tamil language films released so far. ‘Samudayam’ (1962) directed by Henry Chandrawanse was the most recognized Tamil film released up till then.

With establishment of the National Film Cooperation in 1972 by the Samagi Peramuna Government with the new Welfare State Model, 70s was renowned as the hay day of local film industry. But after the open economy was introduced to the country by the regime changes of 1977, followed up by the 1983 brutal anti – Tamil riots and the 30 years of civil war, seized local film industry in to hardships in coming decades. Closure of theatres and studios, time by time curfews, cut off of late night screenings and privatization of distribution created deeper crisis in industry. These issues were deep rooted as far, thus the industry is still struggling to return in to the lines of hope of revival.

Even with prevailing turmoil in the country, promising directors such as Tissa Abeysekara, Wasantha Obeysekara, Dharmasiri Bandaranayeke, H.D Premarathne and many others developed the art of cinema in to a diverse multiplicity in 80s and most of them were able to acquire the IFF attention continuously. With the experience of war and rise of ethnic issue all over the country, early generation of 90s cinema directors, Asoka Handagama and Prasanna Vithanage took another daring twist in local cinema. They managed to get the high attention in regional and international arena. Handagama’s 2001, ‘This is my Moon’ (‘me mage sandai’), was recognized as the third revolution of local cinema. It roller-coastered on the themes of sexuality and politics previously adorned on the path of Dharmasiri Bandaranayake’s cinema of 80s.

Meanwhile, concurrently, director Prasanna Jayakodi was able to create a transcendental type of cinema, through repercussion of varied psychological status of Buddhist thoughts, presenting in a naval way which had attained a rather high IFF attention.

Unfortunately, due to lack of financing and many catastrophes of the prevailing film industry, many young talents such as, Sudath Mahadiwulwewa and Satyajith Maitipe were only capable of making a single debut film in their career. However it should be noted, even during a diabolical period of the film industry, eminent mainstream directors such as, Somarathne Dissanayake and Uadayakantha Warnasooriya were able to grasp a fixed audience strata through their films with different genres.

Among all the dominant male directors in the industry, very few talented female directors were able to create high profiles as directors and one of them pioneering was director Sumitra Peries. Directors Inoka Sthyangani and Sumathi Sivamohan were also to make names for themselves and were able to grasp acclamation by IFF.

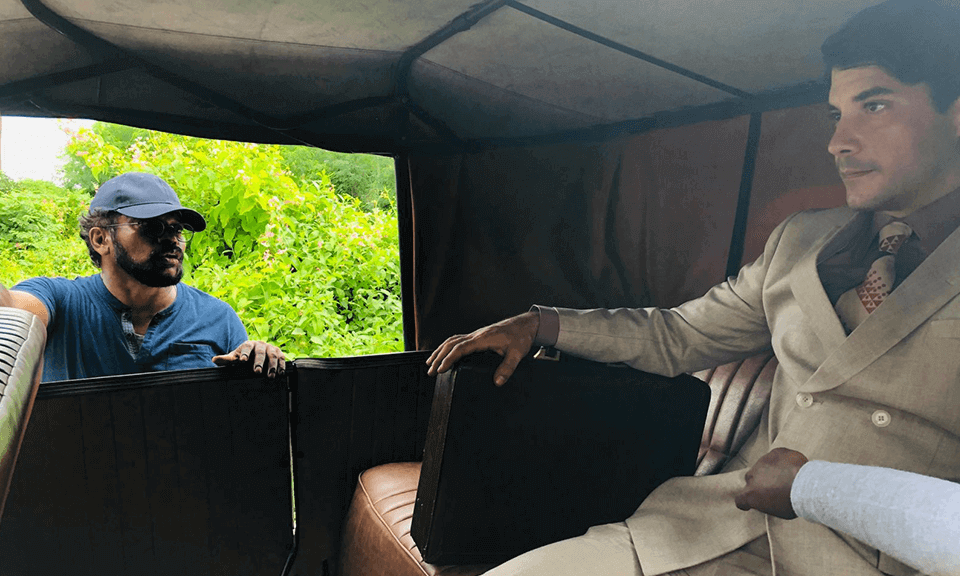

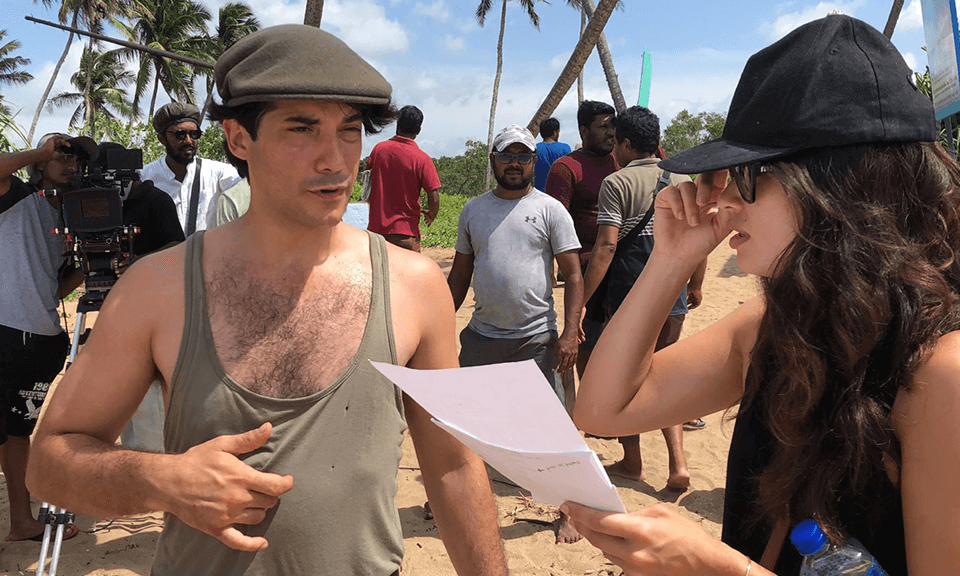

Directors of the millennium are highlighted with the arrival of triumphant international icon Vimukthi Jayasundara who won Camera d’Or at Cannes 2005 for his debut feature ‘Forsaken Land’ (‘Sulanga Enu Pinisa’). Although he managed to follow up with a record of highly successful films, which won many IFF awards, he was perceived highly controversial locally. Subsequently, following Vimukthi’s path Sanjeewa Pushpakumara succeeded internationally with his films and it symbolically ended the era of cinema which was created with the magnanimous effects by the civil war in the country. However, Jude Ratnam was the only other Tamil director to touch the sensitive topic directly again with his groundbreaking documentary ‘Demons in Paradise’ (2018) which was nominated to Camera d’Or at Cannes in 2017.

The post war era of the art house cinema procured a new twist with the release of Shameera Rangana Naotunne’s Motor Bicycle in 2013. It subdued the momentum created by then prevailing domination of mainstream popular politically motivated allegorical epics. When considering the contemporary film directors such as Ariyawanse brothers, Thisara Imbulana, Udaya Dharmawardane, Malith Hegoda, Chinthana Dharmadasa, Udara Abeysundara, Malaka Devapriya and other groups of upcoming young directors, who are motivated on envisaging cinema in to a new era, there is much hope for the future. Ironically, as the popular saying by the G W Friedrich Hegel, ‘History repeats itself.’ one can project that the mainstream cinema is again moving on a direction based on remakes of popular Hindi and Malayalam Cinema, which was the similar case back in early 50s.

Hopefully post pandemic cinema will bring the next radical break in to cinematic presence to Sri Lankan film industry, both politically and substantially since Sri Lanka unavoidably is in the dawn of an era of open global capital structure.